Alex Pennington

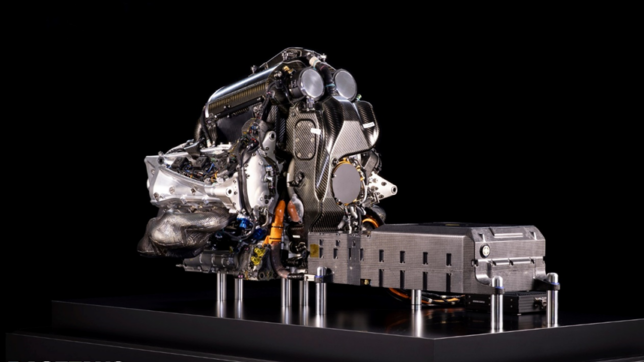

The FIA recently approved the long-awaited engine regulations for 2026, the biggest overhaul since the 2014 introduction of the V6 turbo-hybrids. Following the finalisation of the regulations, Audi has confirmed its entry into the sport in 2026 as an engine manufacturer, with its buyout of Sauber as well as Porsche’s Red Bull partnership expected to follow shortly. With such big changes coming for the whole of F1, let’s take a look at what the regulations actually involve.

Unfortunately, the side effect of all this will be a familiar one in F1’s recent history, and that is increased weight

The big talking point of the new regulations, and F1’s future more generally, is sustainability. The new engines will run on 100% sustainable fuel made from municipal waste and have the same power output as the current generation, at around 1000 horsepower. Another major difference will be the increased reliance on electrical power, with the batteries now providing up to 50% of total power output. This is all in the name of a more sustainable sport with better applications for road cars, which are shifting ever more towards electrical power. However, this will not impact the racing we know and love.

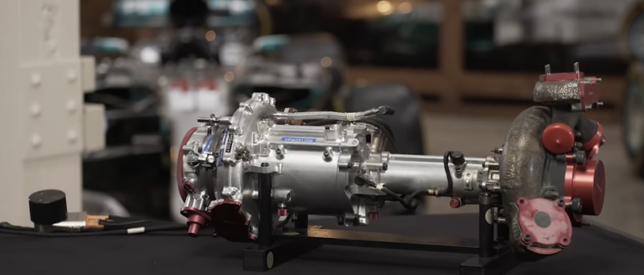

The other change, which is even more significant on the technical side, is the removal of the complicated and expensive MGU-H. The MGU-H is an engine component which uses exhaust gasses to spin a turbine and create energy. This energy is then stored and used to artificially spin up the turbocharger’s air compressor under acceleration. This eliminates turbo lag (the period between acceleration starting, and the turbocharger starting to work to create additional power) and increases the efficiency of the engine. It is, however, a very complex and expensive part to develop, so much so that it has little real-world application and has been a major barrier to new engine manufacturers entering the sport. Its removal was essentially a necessity for Porsche and Audi to agree to enter the sport.

Other changes to the regulations go along with the current drive to reduce costs and improve close racing. There will be a cost cap on engine development (separate to the overall cost cap) of $95m per year from 2023-25 and some parts of the engines, including the engine block and crankshaft, will have development on them tightly restricted. This should help to ensure that performance is relatively similar between engine manufacturers, and that the new manufacturers can enter and be competitive right from the outset.

Unfortunately, the side effect of all this will be a familiar one in F1’s recent history, and that is increased weight. This year’s cars are already 50kg heavier than the previous generation, and the new engines will have much larger battery packs and a move away from expensive, exotic (and lightweight) construction materials. The loss of the MGU-H, on the other hand, will only be worth around 4-5kg.

All of this means that the new engine regs will essentially bring three things: more sustainability; more manufacturers; and more weight. Some drivers and teams have already voiced concern about the weight issue (not to mention the extra money allocated to new manufacturers for development), but on the whole a more sustainable and competitive Formula 1 can only ever be a positive thing. As fans we will just have to accept that the quickest cars in the sport’s history are, at least for now, behind us. If the new engines create close, exciting racing, that seems to be a sacrifice worth making.